“How late did you stay up last night doing your lesson planning?”

“How much instant coffee have you had?”

“Handed out any detentions yet?”

These are just some of the supportive queries I’ve had from my colleagues over the last week and a half, since my daughter stopped going to school along with millions of other pupils in England. As one of the few regular civilians in a team consisting mainly of former teachers, it’s the kind of high-quality sarcasm I’ll just have to get used to as I pick my way through the minefield of home education over the coming months.

Like many other parents I’m unexpectedly in the deep end of home schooling for the first time, trying to find a way of fitting it around work and containing it within the physical and mental confines of isolation during the coronavirus pandemic. My wife and I now split six hours of home school each day, switching our shifts between mornings and afternoons. Work occupies the remaining time, fitting around meals, tidying, government-sanctioned exercise and food shopping, planning the next day’s home school, and trying to teach my mum to use Zoom.

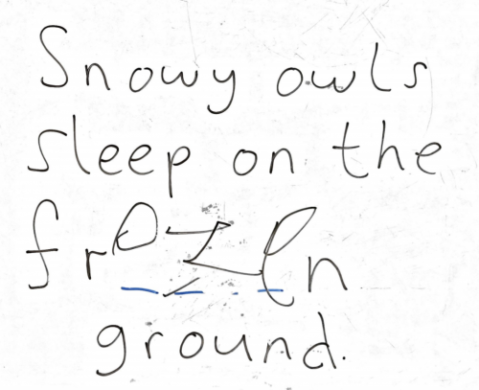

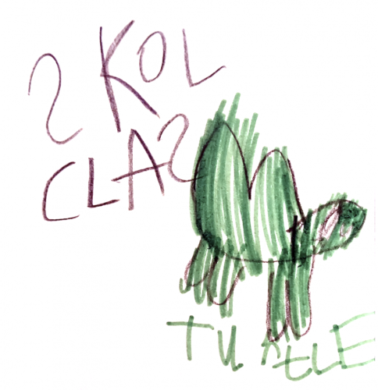

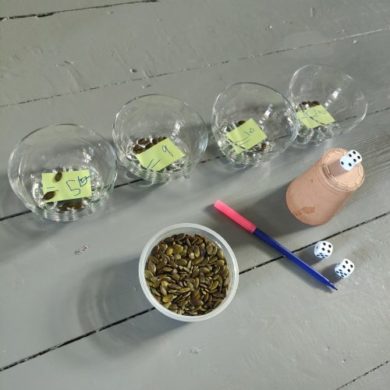

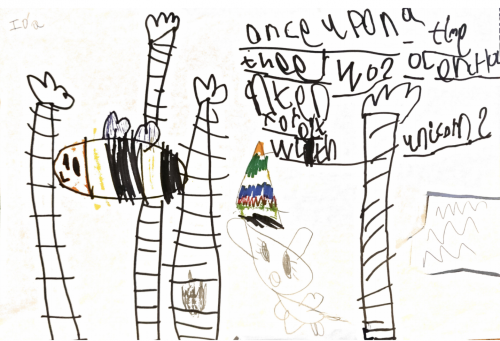

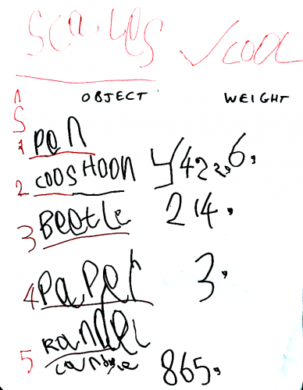

Our daughter is four, so home education is just a case of doing our best to cover the main elements of the Early Years Foundation Stage: mornings are usually a bit heavier with more directed activities with a literacy and numeracy focus, while afternoons have blocks of time for PE, music and things that make a mess. Every few days there might be a video chat with some of the other kids in her class, so there’s a chance to stay connected to her peers. So far we’re surviving well on invented games and role play, ideas and worksheets from the school, inspiration from other home schooling friends on WhatsApp, and the deluge of online resources that have relaxed their paywalls since schools closed. It’s important to us that home school days feel different to the weekend, so every day there’s a printed schedule, a strict 9am start time (apart from the morning my daughter was late because she was “doing her eye shadow”), and the same pattern of snacks, lunch and play breaks. There’s a good amount of self-directed play, but there are also times when we sit at the desk or stand by the whiteboard and focus on something we’ve chosen to focus on. I keep a log of everything we’ve done each day, and use Tapestry to give the school an idea of the things we’re up to.

We’re under no illusion that we can come close to approximating the education a school can provide, and in fact home education offers a chance for a bit of flexibility that schools can’t reasonably accommodate: mucking about, puerile jokes, lots of physical contact, and sudden bursts of loud music and sassy dancing. I even have a new lunchtime running partner. But at the same time, we’ve found that emulating key elements of a school day gives our daughter a sense of continuity and stability, shows that we’re interested in what she’s learning, and demonstrates that we’re taking it seriously.

10 days in, and I already have an even clearer sense of the effort and skill that teachers put into their work, and the demands that the school day places on kids’ energy and concentration. It’s hard work, and it’s testing my patience and ingenuity way beyond their limits. Some days you’re tired before you’ve even started, work is nagging at your mind and things don’t go to plan. But it’s nice to see my daughter learning and developing up close, to see her achievements first hand, and the structure we’ve put in place helps to give all of us a daily rhythm to combat the monotony of being stuck at home.

While I didn’t choose to be in this situation, I’m thankful that my circumstances mean it’s much easier than it could be. I’m privileged. I have a good job that can be easily conducted from home, I’m not having to navigate Universal Credit, and I’m not reliant on Free School Meals to feed my daughter during term time. I’m grateful to have just the one, Reception-aged child at home; to have a nice space in the house we can use as a classroom; access to the sea and the South Downs; a printer; pens and paper; a decent internet connection; a capable partner I can share the timetable with; friends and family we can ask for ideas and activities. And this is where experiences of home education have the potential to diverge dramatically, reflecting the fault lines that exist in our society and the way these play out behind closed doors. This unexpected and protracted period of school closure threatens to expose many young people to significant risk: as the experts at our COVID-19 roundtable last week highlighted, some families face a perfect storm of poverty, domestic abuse, isolation and bereavement over the coming months.

For this reason, alongside the formidable frontline response from schools, local authorities, and voluntary and community organisations, it’s crucial that we examine the impact of school closures over time, on young people, parents and teachers. How are schools supporting families? How are parents and young people coping? What does day-to-day life look like, and how are people feeling about the future? What are the hidden impacts of school closure and how can we address them?

That’s why we’ve collaborated with the Centre for Social Mobility at the University of Exeter to launch a rapid-response programme of research on the impact of school closures, on a wide range of stakeholders. For the first stage of the research, we’re surveying teachers, parents, and students to learn more about their experiences.

We’re looking for as many respondents as possible, and would be hugely grateful if you’re a teacher, widening participation practitioner, parent, or student over the age of 16 and would be willing to take 10 minutes to answer our questions.

We’re hoping to build on the responses to our survey with a programme of detailed qualitative fieldwork, maintaining a dialogue with students and parents over the coming months in order to learn more about how they’re coping with the current situation, what support they would find useful, and whether a set of unprecedented social conditions might have long term consequences for the way we work, educate our children, and live our lives.

This is a repost from the Centre for Education and Youth blog.