There’s unrest in France this week over the government’s plans to raise the retirement age to 64. Every time this debate comes up, it reminds me of all the engrained flaws in the ‘standard model’ working lifecycle. The retirement age is totemic because we spend 45 years of our lives with things out of balance: not enough time for continued learning, and not enough time for ourselves.

The ‘learn-work-retire’ approach is broken

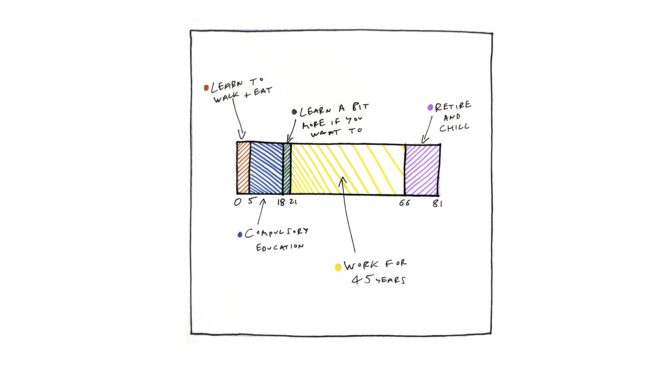

First, we do all our learning in the first two decades of our lives. Then we beaver away doing 36-hour average full-time weeks, for 45 years, squeezing the other aspects of our lives into evenings and weekends. Exhausted, we crawl over the line at 66 and finally get to put our feet up. Play golf. See the grandkids.

That middle ‘work’ phase puts everything out of balance. Most working adults in the UK don’t do any formalised education or training during their careers: employers are spending less and less time and money investing in their employees; the adult education system fell overboard many years ago, and no one even heard the splash. Yes – we learn and develop on the job. And yes, uptake of higher apprenticeships (mainly taken up by older people) is seeing a boost. But for the majority, the ‘learning’ phase of our lives ends when we’re 20 and then we just work. And it’s hardly as though we’re fantastically productive during our 45-year careers: we’re now well into our second decade of lost productivity in the UK. This is partly due to low levels of training and education, poor work-life balance, and low job satisfaction.

The pandemic caused a number of labour market upheavals. Among them, many people dropped down to part time, and started working more flexibly. Half a million people decided to leave the labour market entirely. This exposed some hidden features in our relationship with work: many of us don’t mind our jobs, we just don’t want them to be such a dominant feature in our lives. We might even be happy to work for longer, if things were more in balance when we’re middle-aged: a bit more time for ourselves; a bit more time for learning new skills.

Two retorts I want to acknowledge in advance. First, if you’re on a low wage then you need to work all the hours you can get – and part time isn’t a luxury you can afford. Second, working into your 80s is more viable for non-manual workers. But I don’t think my vision is white collar centric. If we lived in a society where lifelong learning was the norm, and people were regularly undertaking training, we’d be less likely to have such industry-specific careers, to become locked into a particular specialism as we get older, or to have low job satisfaction. A higher skilled workforce also has more earning power.

If we moved to a model where we complete compulsory education at 18, continue formal learning and training throughout our working lives, and work fewer hours a week but until later in our lives, we’d be more productive, have better work-life balance, and be able to start enjoying some retirement-style benefits long before we get to our 60s. If our working lives were more in balance, with more time for ourselves and more time for learning, we’d be happy to work for longer. Work would be a pleasurable part of our lives; something we’d be content to sustain well into old age. In the process, the retirement age would lose its totemic significance.