Maria Miller, Minister for Women and Equality, recently stated her support for reducing the legal time limit for abortions from 24 weeks to 20, reanimating the debate between those who believe the time limit should be reduced and those who believe it should remain as it is. The debate on lowering the legal time limit for abortions involves several different types of argument: moral arguments against ending life, existential arguments about the point at which a foetus attains the status of a human being, rights-based arguments about women’s freedom of choice on matters affecting their health and wellbeing and utilitarian arguments about the impact of late term abortions on the women who have them.

What role can empirical data play in debates like these, which include appeals to absolutes such as rights, morals and values? When it comes to the argument that it is always morally wrong to end a human life, empirical data can provide little by way of counterargument. However, when it comes to Maria Miller’s case for lowering the legal limit, empirical data can offer an instructive rebuttal. Miller’s case is based on two arguments: firstly, medical advances in recent years have increased the odds of survival for premature babies born before 24 weeks; secondly, late-term abortions carried out after 20 weeks have a significant negative impact on women’s wellbeing.

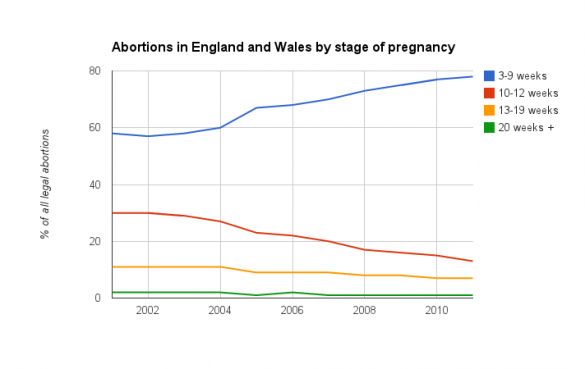

Taking the first argument, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists use data from recent studies to argue that advances in medicine have not, as Miller contends, made it easier for premature babies born before 24 weeks to survive. In the case of the second argument, data from the Department of Health represented in the graph above show that only 1% of abortions in England and Wales in 2011 were carried out after 20 weeks. A change in the law to reduce the time limit for abortions to 20 weeks would therefore prevent what is only a handful of late term abortions from taking place each year. And it is far from clear that preventing these abortions from taking place would lead to an improvement in women’s welfare. The decision to have a late term abortion can only be interpreted as a judgment on the part of the woman concerned that aborting, as awful as it may be for her, is preferable to one or more alternatives: the risk that continuing with the pregnancy could kill both mother and child; that the baby will be born with severe impairments, and so forth. The decision to have a late term abortion is one that, in the abstract, no woman would want to have to take but, in reality, some do when faced with no conceivable alternatives. The welfare effects of a change in the law are far from clear, not only because of the small proportion of abortions that take place after 20 weeks but also because of the individual welfare judgments that lie behind them. Data, and what they represent, can be instructive in even the most intractable of debates.